Cracking the Civil Code

By Farnell Morisset

“And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, [that] all His Majesty’s Canadian Subjects within the Province of Quebec, […] that in all Matters of Controversy relative to Property and Civil Rights, Resort shall be had to the Laws of Canada, as the Rule for the Decision of the same.”

With these words of the Quebec Act, the British government in 1774 enshrined one of the fundamental pieces of Québec’s status as a distinct society. Translated from its lofty 18th-century language, the text confirmed that French civil law (here called the “Laws of Canada” in a flourish of political doublespeak avoiding mention of its origin), and not English common law, would be the law regulating the private lives and relationships of British subjects living in the formerly French colony – English law would be limited to criminal and government matters only. Though other Canadian provinces would grow to adopt (and adapt) English common law for the same private matters, Québec’s civil law tradition continues to govern private interactions within the province to this day.

Widely used throughout the English-speaking world, including in every other Canadian province and most of the United States, common law is a system in which the rules governing interactions between people are developed more or less ad hoc as disputes arise. Whenever a dispute goes to court, the judge will look at past decisions in similar circumstances, evaluate what is common practice, and try to rule in the same way. As a result, the law grows slowly as new cases are brought to courts, and the sum of all past decisions forms the basic rule set for society.

Civil law, on the other hand, has its origins in the rigid legalism of the Roman Empire, and is most common throughout continental Europe and its former colonies. It relies on written codifications of all the rules that govern people, often known as “civil codes” – thousands of rules that are supposed to apply to every conceivable situation. The most famous of these is arguably the Code Napoléon, enacted by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1804 in an attempt to modernize post-revolutionary France. It was Bonaparte’s hope that all French citizens would carry their Code civil des Français around with them and use it to resolve their disputes amicably between neighbours. He insisted that it be written in plain language accessible to every literate French citizen, in stark contrast to the former royal regime’s tendency to use its subjects’ ignorance of the law to its advantage. This code is so famous to this day that people sometimes (incorrectly) refer to Québec’s own laws as the Code Napoléon.

While Québec’s current Civil Code was certainly inspired by Napoleon’s work, it is its own creature. Like many things unique to Québec, it blends French and British elements (it is even officially bilingual) into a cohesive whole, unique to our part of the world. Its more than 3,000 articles are supposed to be the framework governing all private interactions between people in Québec.

Some of its articles, drafted in legalistic language, might even seem comical: it states that children owe respect to their parents (article 597), describes how to split a buried treasure when it is discovered (article 938), legislates that that parents cannot interfere if grandparents spoil their grandchildren (article 611) and that gifts can be taken back if the receiver shows insufficient gratitude (article 1836), and defines newborn animals as “fruit” (article 910) even though animals are explicitly not “things” (article 898.1). In short, Québec’s Civil Code is intended to be an exhaustive attempt at a “good citizen handbook” for the province.

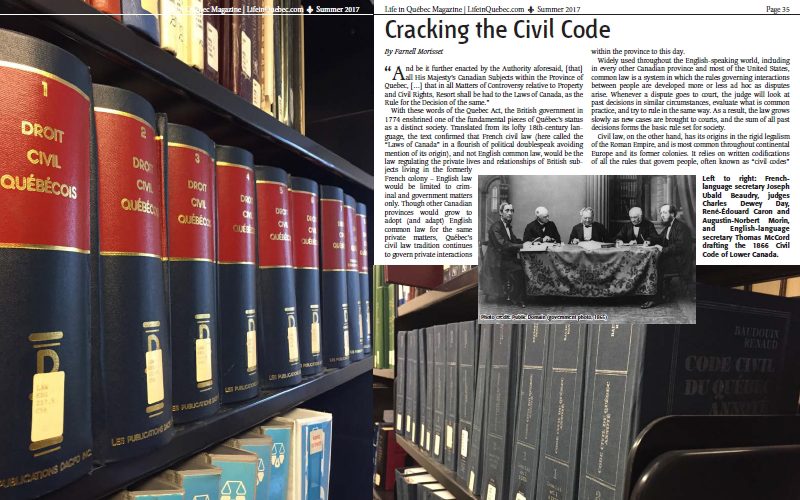

Its status as the guidebook for a proper Québécois life has made the Civil Code at times a highly political document. The first-ever complete codification of Québec’s civil law into a single document, the Civil Code of Lower Canada, came into force in 1866, on the eve of Canadian Confederation, while the second major codification, which gave birth to the modern Civil Code of Québec, came into force in 1994, on the eve of the second Québec sovereignty referendum. This is no coincidence.

In many ways, the Civil Code has historically been a tool of both self-definition and self-affirmation. The 1866 Code enforced Québec’s traditional Catholic values: it gave relatively few rights to married women even in family matters, and presumed inheritance passed from father to “legitimate” son, for instance. Comparatively, the 1994 Code embraced the progressive ideals of modern Québec, facilitating divorce and ensuring equal rights to children of married and unmarried couples.

The Civil Code is also regularly amended by “special laws” passed by the National Assembly as society evolves. A major and much-needed overhaul of the 1866 Code’s archaic and sexist provisions on family law took place in the 1970s, while the 1994 Code was amended in 2002 to allow same-sex unions (three years ahead of the rest of Canada) and more recently in 2015 to recognize that animals were not mere objects, but sentient beings with biological needs.

With each new article, judges and lawyers are sure to pore over the practical effects of the written laws in order to give them meaning. The Civil Code guarantees a right to access a public road from one’s land (article 997), for instance, but is access over a lake sufficient if the owner has a boat? What is the difference between an object that has been lost, which must be returned to its owner (article 940), and an object of minor value that belongs to those who find it (article 934)? Civil law jurists struggle with these questions in a manner that would seem strange, even obsessive, to lawyers and judges in other provinces.

Over time, each article develops its own history of decisions and interpretations, which future judges aren’t technically forced to follow, but which is sure to inform their future decision-making. Interpreting these articles and past decisions also has its own complex set of rules bridging the gap between the French-style laws and British-style courts employed in Québec (helpfully, many of those rules can be found within the Civil Code itself).

As a result of the complex uniqueness of Québec’s legal system, Québec-trained lawyers typically have a harder time practicing in other Canadian provinces that use Common Law (and vice versa). Despite what you might think, it’s not a language issue!

Québec’s proximity to several common law jurisdictions creates a situation in which several universities offer training in both Québec’s civil law system and the common law system of our neighbours. McGill University requires all its graduating law students to be completely at ease with both civil law and common law practice. The University of Ottawa offers complete law programs in either system, while Université de Montréal and Université de Sherbrooke offer additional specializations in common law to budding lawyers completing their training in Québec’s civil law. Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, and Osgoode Hall Law School at York University in Toronto also have partnerships with Québec universities (Université de Sherbrooke and Université de Montréal, respectively) which allow common law students to also receive training in Québec’s civil law.

Québec’s unique system of laws is also one of the reasons why there are always at least three Québec-trained judges sitting on the Supreme Court of Canada, and Québec-trained jurists and legal scholars are often in high demand in federal government positions to make sure that Canadian programs integrate seamlessly into Québec’s private law. When it comes to legal issues, Canada is not only bilingual, it is also bijuridical. Interestingly, the integration of more than one system of laws within a single justice system has also been seen as a blueprint for growing recognition of Aboriginal nations within Canada, and of their right to expand their own systems of law in harmony with the existing Canadian legal framework.

The interaction between English and Roman law frameworks that exists in Québec is not entirely unique in the world. Other former colonies that historically switched hands between the British and other European powers sometimes exhibit a similar trait; Louisiana, for instance, also makes extensive use of civil law despite being in the overwhelmingly common law world of the United States. South Africa, India, and even Scotland also have similar mixtures of common law and local private law. In all cases, the hybridization of legal systems grows and adapts according to each area’s unique history, people and culture.

Today, the Civil Code of Québec remains one of the clearest modern examples of Québec’s distinctiveness. Its presence dates back to the arrival of the very first French settlers in what would become New France, and its safekeeping was important enough to have been a point of contention in negotiations for the capitulation of Montreal at the end of the Seven Years’ War. Today, in modern Québec, it remains as strong as ever.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………………

Would you like to support a project based right here in Quebec?

This book is being co-authored by two people who are passionate about Quebec and everything it has to offer. One of the authors moved to the region some years ago while the other was born and raised in Quebec.

The Québec Book is a unique guide for anyone interested in learning about Quebec culture and the language spoken here. You could be someone visiting Québec, planning to move to Québec, or already living here. Or maybe you’re a native English speaker, a native French speaker, or a speaker of any other language for that matter.

About Author

Write a Comment

Only registered users can comment.